The untold story

Skin For all has created a brief timeline of Medicine’s racial origins ranging from medical practice in the 1800s to policies establishment in the 21st century. The timeline’s purpose is to immerse you in the long embedded story of racism and racial inequalities in medicine/medical education in order to understand why inequalities are still present today and how we can address them as a community. While this list is extensive, it is not fully comprehensive so feedback would be much appreciated.

Disclaimer: The events within this timeline can be triggering due to the nature of many racially prejudiced experiments/ theories so please proceed with caution.

1845

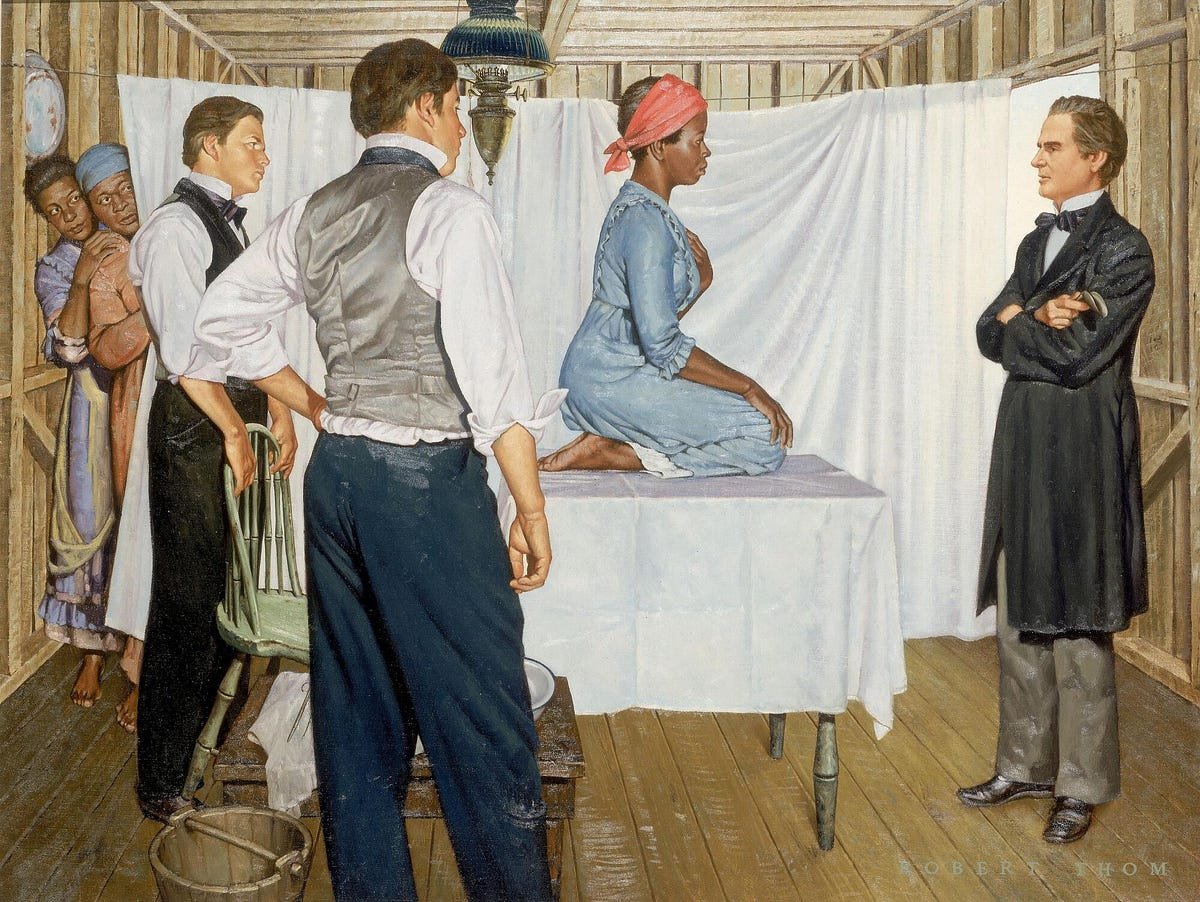

Gynaecological Experimentation on Black Slaves

In 1845, Dr J Marion Sims, an American gynaecologist operated on enslaved women in New York to prove his preconceived notions about pain tolerance between white and black women. His cruel surgeries where performed without consent and anaesthetic. The ignored suffering of pain experiences by Black women can still be seen in contemporary medicine.

Pre- 1865

Undergraduate medical education admission

Medical schools in the Southern states of America were completely closed to Black students, while a select number of northern schools allowed Black students admission. Highlighting the lack of access non-white students were afforded to enter the medical profession.

1910

Flexner report influences medical education

The Flexner Report was a significant assessment of medical education in the US and Canada which impacted multiple areas of medical education, the structure, curriculum and overall criteria regarding the latter. It was detrimental for many Black medical schools as the stricter criteria meant that smaller schools were closed; leading to a reduction in the number of Black physicians and limited access to medical institutions/education for aspiring African-American medical students which retained its impact for years following the Report.

1932

The tuskegee experiment

The US Public Health Service studied 600 men with untreated Syphilis from African-American origins. These men sought medical treatment but were denied Penicillin as the healthcare professionals involved wanted to track the progression of the disease if it was left untreated without the consent of the men infected. This experiment lasted 40 years and unfortunately due to the lack of knowldge behind their condition, the men spread Syphilis to their wife and children. This led to the deaths of 128 men and further severe complications due to the experiment.

1951

Henrietta lacks and the hela cells

Henrietta Lacks was an African American woman who had her cells removed during a biopsy at John Hopkin’s Hospital in 1951 due to an investigation for cervical cancer. These cells were then used for medical research years after her death without her consent or knowledge. Her cells were responsible for the revolution of multiple areas of Medicine such as the relation made between HPV and Cervical Cancer, as well as the mechanism of infection of HIV.

1960’s

Experimentations of Black children

The work of Dr. Orlando J. Andy at the University of Mississippi Medical School in the 1960’s highlighted how Black children with behavioural problems had been treated, discriminated and institutionalised. His procedures included 30 to 40 lobotomies and other brain operations on Black children and other individuals. While Andy stated that his work was a necessary last resort option for people with ‘destructive hyperactivity’, his victims were as young as 6 years old. His work had led to many groups experiencing life-long consequences of reduced neurological capacity.

1969

South Asian women in Coventry being given chapatis containing radioactive iron

South Asian women in Coventry being given chapatis containing radioactive iron in 1969, apparently without their informed consent, during research into higher levels of anaemia in their community. This was one of the many origins of mistrust between healthcare professionals and older South Asian women in the UK. The phenomenon ‘Mrs Begum syndrome’ has led to the dismissal of older Asian women by healthcare professionals as exaggerating their pain.

1960-1970

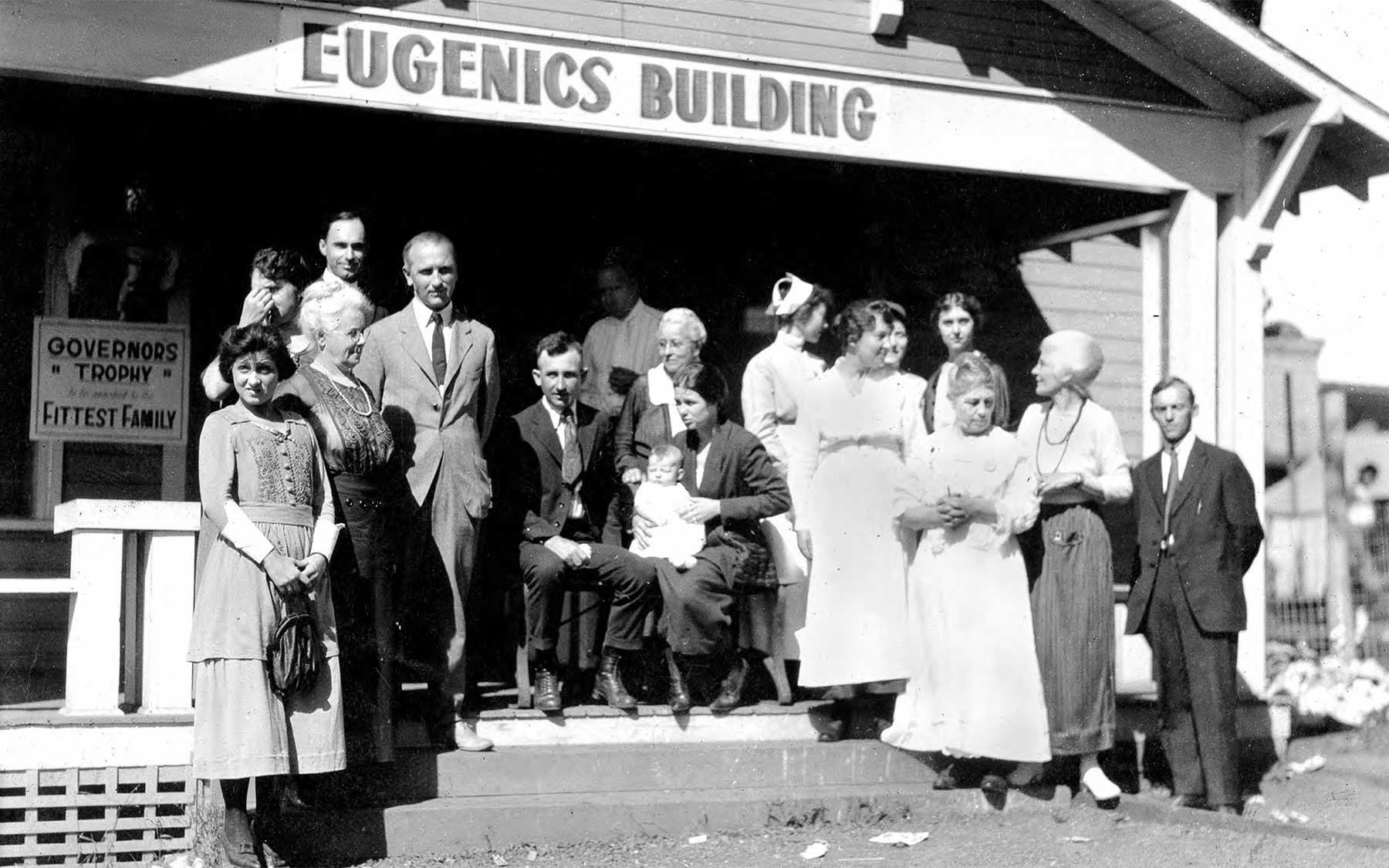

eugenics

In order to reduce the reproductive rates and therefore population size, Black, and Native American women were sterilised without consent. Within prisons, Latina women were highly targeted in years as recent as 1980. Eugenics had become so commonplace that it was referred to as the “Mississippi Appendectomy.” These procedures were done with no consent gained, and healthcare professionals coerced victims as young as 12 to remove their chances of pregnancy; stripping them of their autonomy with their own bodies.

1970-1980

Declaration of Alma AtA

The Declaration of Alma-Ata was released in 1978 to outline the approach needed to achieve “Health For All” by the year 2000. This included addressing and stressing the importance of social justice and equity in health, advocating for fair distribution of health services and resources to address the needs of vulnerable populations.

1990’s

President Bill Clinton

60 years after the start of the Tuskegee study finally issues a formal apology to the victims of the trials. This was after heavy petitioning by Black and White public health officials, activists, family members of the victims of the trials and some of the victims themselves.

2003

The Human Genome Project

The project confirms that race has no biological basis but emphasises the importance of considering social factors in health disparities.

2006

Race for health

The National Health Service (NHS) in the UK implements strategies to tackle racial inequalities in healthcare delivery, including addressing disparities in access to services and healthcare outcomes among different ethnic groups.

2019-2023

Black Lives matter and the disproportionate death toll of ethnic minority communities due to COVID-19

The Black Lives Matter movement grew in response to the systemic oppression and discrimination faced by Black individuals by institutions like the police force. Th movement gained momentum across the globe and an international call was made to address the structural racism embedded within society derived from racist and biased narratives created by colonialist powers. This included policy change, a call for greater accountability of cases of racial discrimination and a structural change to the previously colonialist views about society.

With the commencement and growth of the COVID 19 pandemic, people from Minority Ethnicities faced structural inequalities, which limited their access to healthcare, economic disparities, and a higher prevalence of underlying health conditions. There was also a greater risk of mortality placed on Ethnic Minority individuals due to a greater risk of severe illnesses from the virus. Additionally, systemic racism in healthcare systems and social determinants of health had contributed to unequal outcomes during the pandemic and a greater death toll for Ethnic Minority individuals compared to their White counterparts.

2016

Medical student perceptions

University of Virginia students believe black and white patients are biologically different. Highlighting the impact historically biased/ prejudiced events had on contemporary education and student perceptions.

Present day

The legacy of racism in medical education

The consequences of racism in medicine can be seen in contemporary society with UK stats highlighting that medical students and junior doctors from ethnic minority backgrounds experience significantly more micro-aggressions, discrimination, and mistreatment than their White colleagues. in the US, non-White medical students and residents (Senior House Officers in the UK) consistently receive lower clinical performance scores than White peers. It was also found in the US in 2021 that 75% of full professors at medical schools were White and 60% of medical school department chairs were White and male.

When addressing racial bias in medical education, the fight isn’t isolated to individual implicit bias, but centuries of historical events and political efforts that have shaped American and European medicine into a space favours White, male figures/ideologies. Therefore, as a community, we cannot significantly dismantle racial bias in medical education without confronting its historic origins.

Thankfully, inspiring organisations like White Coats for Black Lives, and Melanin Medics. These cohorts work towards dismantling the systemic racism grown within the medical system by supporting students with informative content and opportunities to thrive within this system. Literature such as Divided by Reproductive Justice founder and medical doctor, Annabel Sowemimo and Mind the Gap by medical student, Malone Mukwende have also tackled the topics of healthcare bias. Pushing forward the message of a future with equal knowledge and risk perception of diseases on all skin tones.

In this movement towards diversifying the medical sphere, it is important to equip readers and aspiring activists with the tools needed to continue this journey and ensure it is as sustainable as possible. Students can help support this movement by calling for more cases regarding ethnic minority patients to be integrated within their course material. A call for the inclusion of images and recommended reading lists will further enable the normalisation of diversity. By encouraging those to engage with the conversations, speeches, materials, articles and people dedicated to the cause, we can create a culture within medical education that not only includes diversity in its teaching but accepts it as commonplace means that students from a multitude of backgrounds and ethnicities can be educated in an environment where they feel represented and a sense of belonging.